Protective Dissociation and Scam Victims

Protective Dissociation in Scam Victim Recovery – Enabling the Impossible and Protecting from Too Much

Primary Category: Scam Victim Recovery Psychology

Authors:

• Vianey Gonzalez B.Sc(Psych) – Licensed Psychologist, Specialty in Crime Victim Trauma Therapy, Neuropsychologist, Certified Deception Professional, Psychology Advisory Panel & Director of the Society of Citizens Against Relationship Scams Inc.

• Tim McGuinness, Ph.D., DFin, MCPO, MAnth – Anthropologist, Scientist, Polymath, Director of the Society of Citizens Against Relationship Scams Inc.

Author Biographies Below

About This Article

Protective dissociation is a trauma-related nervous system response that reduces emotional and sensory overload when psychological intensity becomes unmanageable. In scam victims, it commonly appears during the grooming and manipulation, discovery, and aftermath phases of the scam, where betrayal, shame, and identity disruption collide. Unlike denial, protective dissociation does not reject facts but limits emotional access to prevent overwhelm. It overlaps with peritraumatic and trauma-related dissociation and can exist without a dissociative disorder. While adaptive in the short term, persistent dissociation can interfere with recovery by blocking emotional integration. Effective healing focuses on restoring safety, pacing emotional access, reducing shame, and supporting nervous system regulation rather than forcing awareness. When safety increases, dissociation often decreases naturally as integration becomes tolerable again.

Note: This article is intended for informational purposes and does not replace professional medical advice. If you are experiencing distress, please consult a qualified mental health professional.

Protective Dissociation in Scam Victim Recovery – Enabling the Impossible

What is Protective Dissociation

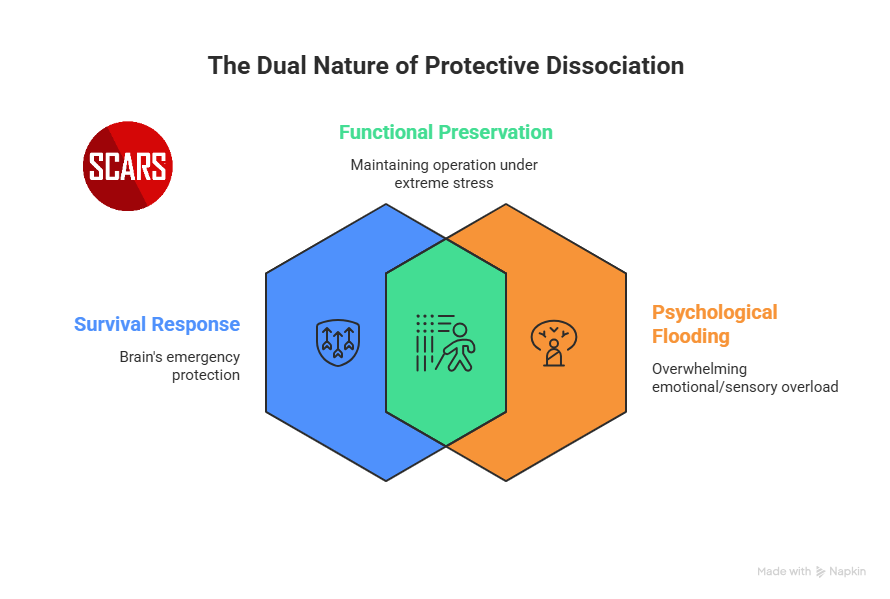

Protective dissociation is a survival response where the brain reduces emotional and sensory overload so a person can keep functioning during danger, intense stress, or an experience that feels unendurable. It can look like emotional numbness, “going blank,” feeling detached from the body, losing track of time, or operating on autopilot. It is not a character flaw, a weakness, or a sign of “craziness.” It is the nervous system doing what it can to protect the person from being psychologically flooded.

This protective function matters for scam victims because relationship scams can create a unique form of psychological injury. Many survivors are not only grieving a loss. They are also processing betrayal trauma, shame, identity disruption, and a sudden collapse of perceived safety. In that kind of impact, the mind may choose disconnection as an emergency brake. The goal is not to escape life. The goal is to reduce unbearable intensity long enough to survive the moment, make decisions, and keep going.

Protective dissociation is often misunderstood because it can feel like the person is “not reacting normally.” In reality, it is a normal human response to abnormal stress. It may happen during the scam while manipulation is happening. It may happen when the scam collapses and reality hits. It may also happen later, when triggers bring the nervous system back into the same threat state.

How Protective Dissociation Works

Dissociation, including protective dissociation, is not one single thing. It is a set of processes that alter attention, awareness, memory, perception, and emotional connection. At a simple level, the brain shifts resources away from deep feeling and complex reflection and toward short-term survival. This can create a sense of distance from the self, the environment, or time.

Neurologically, dissociation is linked to changes in how the brain integrates experience. When stress becomes extreme, the nervous system can move into defensive states. Some people recognize the fight response, the flight response, and the freeze response. Dissociation often tracks most closely with freeze and shutdown responses, where the system reduces energy output and reduces emotional access as a form of protection. This does not mean the person is safe. It means the brain is trying to make the experience tolerable.

A practical way to explain it is this. During high threat, the brain prioritizes survival over meaning. It narrows focus. It changes time perception. It may dull pain and emotion. It may reduce access to narrative memory and increase fragmented memory. The body may feel far away or unreal. The person may look calm while internally they are overwhelmed. This mismatch can confuse survivors and their families because “calm” can actually be shutdown.

Why Protective Dissociation Affects Scam Victims

Relationship scams injure the attachment system. They exploit bonding, trust, hope, and the human need for connection. When the betrayal is exposed, many victims experience a sudden collision of realities. They must reconcile memories of affection and intimacy with proof of deception. That conflict can overload the brain’s capacity to integrate emotion, identity, and meaning.

This is why dissociation can become a common response. The brain may say, “This is too much to feel all at once,” and it begins to compartmentalize. Some victims describe feeling emotionally flat, as if they are watching their life from outside. Others describe feeling foggy, unable to think clearly, unable to focus, or unable to remember what they just read. Some describe sudden waves of unreality. Others describe a deadened emotional field where grief feels distant, even though it is still there.

This can be protective in the short term. It can also become a barrier when it persists. When the nervous system stays in shutdown, healing slows because processing requires safe contact with feelings, memory, and meaning.

What Makes “Protective Dissociation” Different From Other Forms of Dissociation

A useful distinction is purpose and timing.

Protective dissociation emphasizes the function of dissociation as a defensive strategy. It is dissociation that shows up because the nervous system believes it must reduce intensity to prevent overwhelm, collapse, or panic. It is a built-in protective mechanism.

Regular dissociation in trauma, including what many survivors experience, is also protective at first. The difference is that trauma-related dissociation can become habitual, generalized, or triggered by reminders long after danger is over. It may appear in everyday situations where the person is not actually unsafe, but the nervous system is still interpreting cues as threats.

So the distinction is not that protective dissociation is “good” and other dissociation is “bad.” The distinction is that protective dissociation is often the initial emergency response, and trauma-linked dissociation can become a learned pattern that continues after the crisis.

Another difference is awareness and control. In protective dissociation, the person may not realize what is happening because the mind is prioritizing functioning. In chronic trauma-related dissociation, the person may begin to notice patterns, such as always “checking out” when conflict happens, when shame rises, or when intimacy appears. That pattern can become reinforced, because dissociation brings short-term relief, even when it creates long-term costs.

A third difference is integration. Protective dissociation often happens when the brain cannot integrate experience in real time. It is a temporary separation, like putting the experience in a box until it can be handled. If the person later processes the event in safety, the box can be opened and integrated. If the person never has adequate support, never has safety, or stays in a state of shame and self-blame, the box stays sealed. This can contribute to persistent symptoms.

How Dissociation During Trauma Differs from Protective Dissociation

Many clinicians use “dissociation during trauma” to describe what happens at the moment of the traumatic event. A person may feel detached, numb, unreal, or as if time slowed. This is often called “peritraumatic dissociation,” meaning dissociation that occurs during or immediately around the trauma.

Protective dissociation overlaps with this concept, but it is broader. Protective dissociation is not limited to the exact moment of trauma or its aftermath. It can occur in anticipation of threat, during sustained stress, and after trauma when triggers or flooding begin. It is still the same protective logic, even if it happens later. The nervous system is trying to prevent emotional overload and collapse.

For scam victims, this distinction matters because the scam is not a single event. It is often prolonged coercion, grooming, and manipulation. The “trauma” can be cumulative. A victim may dissociate during the grooming phase, especially when instincts conflict with hope. They may dissociate during the collapse phase, when evidence arrives. They may dissociate during the aftermath, when shame, grief, and fear spike. Each phase can trigger the same protective shutdown.

So, peritraumatic dissociation describes timing. Protective dissociation describes function.

What Dissociation Looks Like in Scam Victim Recovery

Trauma survivors often describe dissociation as “spacing out.” That is real, but it can be more specific than that. For scam victims, dissociation may show up as:

- Emotional numbing, where feelings disappear or feel distant.

- Cognitive fog, where thinking becomes slow, disorganized, or unreliable.

- Time loss, where hours pass without awareness.

- Memory gaps, especially around painful moments or specific triggers.

- Depersonalization, where the person feels detached from the self or body.

- Derealization, where the world feels unreal, distant, or dreamlike.

- Autopilot functioning, where tasks happen without a sense of presence.

- Trigger shutdown, where certain words, sounds, images, or topics cause sudden disconnection.

These are not moral failures. They are signals that the nervous system believes it needs protection. The goal is to interpret them correctly, then build safety so the system no longer needs to shut down.

Why the Brain Uses Dissociation Instead of Feeling

The brain makes tradeoffs under stress. In a safe state, the brain can hold complexity. It can feel grief, reflect, problem-solve, and connect. In high threat, the brain shifts into survival priorities. When that survival state becomes extreme, the brain may reduce conscious access to emotion and sensation.

This happens because feeling is metabolically and psychologically expensive. Grief, shame, fear, and rage require integration across brain systems. When the brain predicts that the person will be overwhelmed, it shifts into protective strategies. Dissociation reduces the felt intensity, even when the underlying threat perception remains.

This is also why dissociation can feel confusing. The person may say, “I know this is terrible, but I cannot feel it,” or “I feel nothing, and that scares me.” That mismatch is common. Cognition and emotion can temporarily split.

Dissociation Appearing as Denial

Protective dissociation can very easily appear to an outsider as denial, even though psychologically they are not the same process.

Why It Looks Like Denial From the Outside

From the outside, protective dissociation often looks like a person is refusing to face reality, minimizing what happened, or emotionally disengaging from obvious consequences. Friends, family, or even professionals may say things like, “They are in denial,” or “They are not dealing with this.” What they are seeing is distance, flat affect, reduced emotional reaction, or a lack of urgency.

Protective dissociation creates this appearance because the person is not fully accessing the emotional meaning of the event in the present moment. The nervous system has reduced emotional input to prevent overload. To an observer, this can look like indifference, avoidance, or intellectualization. In reality, the person’s system is still processing threat and loss, just not in a way that is visible or dramatic.

Denial is a cognitive defense. Protective dissociation is a nervous system response.

The Core Difference Between Denial and Protective Dissociation

- Denial involves rejecting, distorting, or minimizing facts. A person in denial may insist that something did not happen, was not serious, or does not matter. The mind is actively defending against information.

- Protective dissociation does not require rejecting facts. Many dissociating victims fully acknowledge what happened at an intellectual level. They can describe the scam, name the losses, and explain the consequences. What is missing is emotional access, not awareness.

In other words, denial blocks knowing. Protective dissociation blocks feeling.

This is why a scam victim may say, “I know what happened, but I do not feel it,” or “I understand this was devastating, but I feel strangely numb.” That statement would not fit denial, but it fits dissociation very well.

Why Outsiders Misinterpret It

Most people expect grief and trauma to look emotional. They expect tears, anger, agitation, or visible distress. When someone does not display those reactions, observers assume the person is suppressing, avoiding, or refusing to engage.

Protective dissociation disrupts those expectations. The person may appear calm, detached, or even functional. They may focus on logistics, paperwork, or routine tasks. This outward functioning is often misread as coping or denial, when it is actually survival-mode regulation.

There is also a cultural bias that equates emotional expression with honesty and emotional restraint with avoidance. That bias increases mislabeling, especially when the trauma is complex or stigmatized, as scams often are.

Why the Mislabel Matters

Labeling protective dissociation as denial can cause real harm. It can lead to pressure, confrontation, or shaming, which increases threat and pushes the nervous system deeper into shutdown. Statements like “You need to face reality” or “Stop avoiding your feelings” often backfire because the person is not choosing avoidance. Their system is protecting them.

For scam victims, this misinterpretation is especially dangerous because shame is already high. Being accused of denial can reinforce self-blame and increase isolation, which prolongs dissociation rather than resolving it.

How Protective Dissociation Resolves

Protective dissociation resolves through safety, not confrontation.

As the nervous system learns that it can tolerate emotion without being overwhelmed, emotional access gradually returns. This often happens in waves, not all at once. The return of feeling can be delayed, and it can surprise both the victim and those around them.

Supportive responses sound like:

- “I see that this is a lot.”

- “You do not have to feel everything at once.”

- “We can take this step by step.”

These responses reduce threat and allow the protective response to relax.

Key Distinction to Remember

- Denial is a refusal to accept reality.

- Protective dissociation is a temporary loss of emotional access to reality.

They may look similar from the outside, but they come from entirely different systems in the brain. Understanding that difference helps families, professionals, and victims respond in ways that support healing rather than unintentionally slowing it.

What Are the Classifications of Psychological Dissociation

Dissociation can be described in several classification systems and clinical frameworks. The most useful approach for victims is to understand it in layers, from common experiences to clinical disorders.

Non-Pathological Dissociation

This is everyday dissociation that occurs without trauma. It includes daydreaming, “highway hypnosis,” and becoming absorbed in a book or movie. The person’s attention narrows, but identity remains stable, and functioning is intact. This is not a disorder.

Trauma-Related Dissociation

This includes dissociative responses linked to threat, trauma, or chronic stress. It may include depersonalization, derealization, emotional numbing, and memory fragmentation. It can occur during trauma and after trauma, especially when triggers activate threat circuitry.

Peritraumatic Dissociation

This is dissociation occurring during or immediately after a traumatic event. It can include feeling detached, unreal, or numb, and it may include altered time perception. In some studies, strong peritraumatic dissociation is associated with higher risk for later post-traumatic symptoms, though each person’s outcome varies.

Structural Dissociation

This is a framework that describes dissociation as a division between parts of experience, often between daily functioning and traumatic memory. A person may have an “apparently normal” part that handles life and an “emotional” part that holds trauma responses. This model is often used to explain why trauma can feel both “over” and “still happening” in the body.

Dissociative Symptoms

These are symptom categories often discussed in clinical contexts:

- Depersonalization symptoms: detachment from self, body, or emotions.

- Derealization symptoms: detachment from surroundings, unreality of the world.

- Amnesia symptoms: memory gaps, lost time, inability to recall important events.

- Identity confusion: uncertainty about self, values, preferences, or continuity.

- Identity alteration: shifts in sense of self, sometimes including distinct parts.

- Absorption: intense narrowing of attention, sometimes used to escape distress.

Dissociative Disorders

These are clinical diagnoses, typically considered when dissociation is persistent, impairing, and not better explained by substances or medical causes.

- Dissociative Amnesia: Dissociative amnesia refers to a disruption in the ability to recall important autobiographical information that would normally be accessible, especially information connected to traumatic or overwhelming experiences. The memory loss is not due to ordinary forgetting, brain injury, or substance use. Instead, the nervous system restricts access to memory as a protective response. The person may forget specific events, time periods, or personal details while remaining otherwise cognitively intact. This condition reflects how the brain can separate memory from awareness when emotional overload exceeds coping capacity.

- Depersonalization and Derealization Disorder: Depersonalization and derealization disorder involves persistent or recurrent experiences of feeling detached from one’s own self, one’s emotions, or the surrounding world, while reality testing remains intact. Depersonalization feels like observing oneself from the outside or feeling emotionally numb or unreal. Derealization involves the perception that the external world looks flat, distant, artificial, or dreamlike. The individual knows these sensations are not literally true, which often increases distress. These symptoms reflect chronic nervous system dysregulation rather than psychosis or denial.

- Dissociative Identity Disorder: Dissociative identity disorder involves a severe disruption in identity characterized by the presence of distinct self-states, each with its own patterns of perception, emotion, and behavior. These self-states may have limited awareness of one another, leading to memory gaps or discontinuities in everyday life. This condition is strongly associated with repeated, overwhelming trauma in early development, when the brain had not yet formed an integrated sense of self. The dissociation serves as a survival strategy that allows psychological functioning to continue under extreme threat.

- Other Specified Dissociative Disorder: Other specified dissociative disorder is diagnosed when dissociative symptoms cause significant distress or impairment but do not meet the full criteria for a specific dissociative disorder. This category includes mixed or atypical presentations, such as identity disturbance without clear memory gaps or dissociative symptoms tied to specific triggers rather than being constant. It acknowledges that dissociation exists on a spectrum and that clinically meaningful dissociation can occur without fitting rigid diagnostic boundaries. This diagnosis is often used when trauma-related dissociation is evident but complex.

- Unspecified Dissociative Disorder: Unspecified dissociative disorder is used when dissociative symptoms are clearly present and disruptive, but there is insufficient information to determine a more specific diagnosis. This may occur in crisis settings, early assessments, or situations where a full trauma history cannot yet be safely explored. The diagnosis reflects caution rather than uncertainty about the presence of dissociation. It allows clinicians to recognize and address dissociative processes while prioritizing stabilization, safety, and further evaluation as trust and capacity for assessment develop.

Many scam victims experience dissociative symptoms without meeting criteria for a dissociative disorder. That distinction is important because symptoms can be real and distressing without being a formal disorder.

How Protective Dissociation Fits Into These Classifications

Protective dissociation is not a separate diagnostic category and does not appear as a stand-alone diagnosis in clinical manuals. It is a functional description that explains why dissociation occurs, rather than what diagnostic label applies. Protective dissociation refers to the nervous system’s use of dissociative mechanisms to reduce psychological overload when perceived threat, emotional intensity, or cognitive conflict exceeds a person’s capacity to cope in the moment.

Protective dissociation most often appears within trauma-related dissociation, including peritraumatic dissociation that occurs during or immediately after a traumatic event. It can also be present across recognized dissociative conditions, such as dissociative amnesia, depersonalization and derealization, or identity-related disruptions. In each case, the dissociation serves the same core function, which is to preserve psychological stability and functioning when full awareness would be overwhelming or destabilizing.

Protective dissociation exists on a spectrum. In mild or time-limited forms, it may involve brief emotional numbing, mental distancing, or narrowed awareness that resolves once safety returns. In these cases, dissociation can be adaptive and self-limiting. When protective dissociation becomes chronic, rigid, or generalized, it can interfere with memory integration, emotional processing, and daily functioning. The original protective purpose remains, but the nervous system continues to act as though danger is ongoing. Understanding protective dissociation in this way helps separate intent from outcome, reducing self-blame while clarifying why healing requires restoring safety rather than forcing awareness.

What To Watch For

Protective dissociation may be helpful in a crisis, but it becomes risky when it blocks recovery. Warning signs that dissociation is becoming a barrier include:

- Frequent loss of time or memory gaps that cause safety concerns.

- Persistent feelings of unreality or detachment that do not improve.

- Inability to access emotions at all, even in safe settings.

- Significant impairment in work, relationships, decision-making, or self-care.

- Dissociation triggered by minor stressors, not only major reminders.

- Increased isolation because the person feels too disconnected to engage.

If these signs are present, trauma-informed clinical support can be important.

What To Do Next

For many scam victims, the first step is not forcing feelings. The first step is building stability and safety so the nervous system does not need to shut down.

A practical approach includes:

- Grounding skills: sensory orientation, temperature shifts, paced breathing, body contact with stable surfaces.

- Reality anchoring: naming the date, location, and immediate facts to counter derealization.

- Trigger mapping: identifying the cues that lead to shutdown, including topics, places, and body sensations.

- Gentle emotion access: small doses of feeling with containment, not emotional flooding.

- Shame reduction: separating crime victimization from identity and worth.

- Professional support: trauma-informed therapy for persistent dissociation, especially when memory gaps or safety concerns exist.

Recovery Notes and Resources

Dissociation is the nervous system’s way of communicating that experience has exceeded its current capacity for integration. When a situation feels emotionally, cognitively, or physiologically overwhelming, dissociation allows the system to reduce intensity so survival and basic functioning can continue. Protective dissociation is not a failure or a weakness. It reflects an adaptive response that once helped preserve stability during periods of threat, betrayal, or prolonged stress.

For recovery to occur, the goal is not to eliminate dissociation by force or to push awareness faster than the body can tolerate. Healing happens when the nervous system gradually learns that it can remain present without being flooded. This process requires pacing, predictability, and a sense of safety that is experienced in the body, not just understood intellectually. When safety becomes consistent, the need for dissociation often decreases on its own.

Structured routines help by reducing uncertainty and restoring a sense of control. Stable support, whether through trauma-informed therapy, peer support groups, or trusted relationships, provides external regulation while internal regulation is rebuilt. Compassionate education about trauma responses reduces shame and helps survivors understand that their reactions are normal responses to abnormal circumstances. Over time, these supports allow emotional processing to occur in manageable segments, helping awareness return without reactivating threat responses.

Key Takeaways

- Protective dissociation is a survival strategy that reduces overwhelm during intense stress or threat.

- Dissociation during trauma describes timing, while protective dissociation describes function.

- Many scam victims experience dissociative symptoms without having a dissociative disorder.

- Dissociation can be adaptive short term but can block healing if it persists.

- Grounding, shame reduction, and trauma-informed care help the nervous system reintegrate.

Conclusion

Protective dissociation explains why many scam victims continue functioning in the face of overwhelming betrayal, loss, and psychological shock. It is not denial, avoidance, or weakness. It is a nervous system strategy designed to prevent collapse when emotional and cognitive load exceeds capacity. Understanding this response reframes dissociation from something to fight into something to respect and work with. Recovery does not require forcing awareness or emotion before safety is restored. It requires helping the nervous system relearn that presence is no longer dangerous. With pacing, education, reduced shame, and consistent support, dissociation often softens naturally. As integration returns, feelings, memory, and meaning can reconnect without flooding. Protective dissociation kept the person going when survival demanded it. Healing begins when protection is no longer the only option.

Glossary

- Absorption — Absorption is a narrowed focus of attention where awareness of surroundings fades while attention locks onto a task, thought, or internal experience. In scam victims, absorption can function as a temporary escape from emotional overload but may also reduce awareness of stress signals.

- Acute Stress Load — Acute stress load refers to the total physiological and psychological strain placed on the nervous system during intense threat or crisis. High acute stress load increases the likelihood of dissociation, cognitive fog, and emotional shutdown.

- Alarm System — The alarm system is the brain and body network responsible for detecting danger and initiating survival responses. After a scam, this system may remain hypersensitive and trigger dissociation even in safe situations.

- Alexithymia-Like Response — An alexithymia-like response involves difficulty identifying, naming, or describing emotions during periods of stress. Scam victims may experience this temporarily when protective dissociation reduces emotional access.

- Anticipatory Dissociation — Anticipatory dissociation occurs when the nervous system disconnects in advance of an expected emotional threat. It often appears before difficult conversations, reminders of loss, or shame-related events.

- Attachment Injury — Attachment injury refers to damage to the psychological system that governs trust, bonding, and emotional safety. Relationship scams create attachment injury by pairing intimacy with exploitation and betrayal.

- Autonomic Dysregulation — Autonomic dysregulation is the loss of flexible balance between activation and calming states. When dysregulated, the nervous system may swing between anxiety and shutdown without conscious control.

- Autopilot Functioning — Autopilot functioning describes completing tasks without emotional presence or memory richness. It allows survival-level functioning but often increases exhaustion and memory gaps.

- Body Detachment — Body detachment is the sensation of being disconnected from bodily sensations or physical presence. It commonly appears during intense shame, fear, or emotional overload.

- Cognitive Fog — Cognitive fog involves slowed thinking, impaired concentration, and reduced mental clarity. It reflects survival prioritization rather than intellectual failure.

- Cognitive Load — Cognitive load refers to the amount of mental effort required to process information and regulate emotion. When cognitive load exceeds capacity, dissociation becomes more likely.

- Compartmentalization — Compartmentalization is the mental separation of painful information from daily awareness. It allows short-term functioning but delays emotional integration if it persists.

- Cumulative Trauma — Cumulative trauma develops through repeated or prolonged stress rather than a single event. Relationship scams often create cumulative trauma through ongoing manipulation and deception.

- Defensive Numbing — Defensive numbing is a protective reduction in emotional intensity that limits pain perception. It may appear calm externally while masking significant internal distress.

- Denial — Denial is a cognitive defense involving rejection or minimization of factual reality. It differs from dissociation, which limits emotional access rather than awareness.

- Depersonalization — Depersonalization is a dissociative experience marked by feeling detached from one’s own thoughts, emotions, or body. Reality testing remains intact.

- Derealization — Derealization involves a perception that the external world feels unreal, distant, or artificial. The person understands the sensation is subjective, which often increases distress.

- Dissociation — Dissociation is a disruption in the integration of awareness, memory, emotion, perception, or identity. It functions as a protective response to overwhelming stress.

- Dissociative Amnesia — Dissociative amnesia involves the inability to recall important autobiographical information related to trauma. The memory loss reflects nervous system protection rather than brain injury.

- Dissociative Identity Disruption — Dissociative identity disruption refers to instability or fragmentation in the sense of self without full identity separation. It can occur in severe trauma without meeting diagnostic thresholds.

- Emotional Flooding — Emotional flooding is an intense surge of feeling that overwhelms coping capacity. Dissociation often activates to prevent collapse during flooding.

- Emotional Numbing — Emotional numbing is reduced access to feelings, especially grief or fear. It signals protective shutdown rather than emotional absence.

- Energy Conservation Response — Energy conservation response is a shutdown state that lowers physiological output to survive a threat. It often appears as fatigue or calm disengagement.

- Fragmented Memory — Fragmented memory refers to disjointed recall of events without narrative continuity. High stress disrupts normal memory integration.

- Freeze Response — Freeze response is a survival state marked by immobility, reduced speech, and narrowed awareness. Dissociation often accompanies freeze.

- Grounding — Grounding is the practice of reconnecting awareness to present sensory and physical cues. It helps reduce dissociation by restoring safety signals.

- Hypervigilance — Hypervigilance is constant scanning for threat even in safe environments. It frequently coexists with dissociation in trauma survivors.

- Identity Disruption — Identity disruption is a destabilized sense of self following betrayal or trauma. Scam victims may question judgment, worth, and personal history.

- Integration — Integration is the process of linking emotion, memory, body sensation, and meaning into a coherent whole. Recovery depends on gradual integration.

- Narrative Memory — Narrative memory is the ability to organize experience into a coherent story. Dissociation disrupts narrative memory under stress.

- Peritraumatic Dissociation — Peritraumatic dissociation occurs during or immediately after traumatic events. It is associated with altered time perception and emotional detachment.

- Protective Dissociation — Protective dissociation is a functional description of dissociation used to reduce overwhelm and preserve functioning. It reflects nervous system defense rather than pathology.

- Reality Anchoring — Reality anchoring involves orienting to current facts such as date, location, and surroundings. It counters derealization and shutdown.

- Shame-Based Shutdown — Shame-based shutdown occurs when intense self-blame triggers dissociation. Scam victims are particularly vulnerable due to stigma and self-judgment.

- Structural Dissociation — Structural dissociation describes the separation between functioning parts and trauma holding parts of the experience. It explains why trauma feels both past and present.

- Survival Mode — Survival mode is a nervous system state focused on immediate safety rather than meaning or reflection. Dissociation supports survival mode functioning.

- Threat Appraisal — Threat appraisal is the brain’s evaluation of danger. After scams, threat appraisal often remains elevated and triggers shutdown responses.

- Time Distortion — Time distortion involves an altered perception of time passing too fast or too slow. It commonly accompanies dissociative states.

- Tolerance Window — Tolerance window is the range of emotional intensity a person can manage while staying present. Protective dissociation appears when this window is exceeded.

- Trigger — A trigger is any cue that activates trauma-related responses. Triggers can be internal or external and often provoke dissociation.

- Trauma Bond — Trauma bond is an attachment formed through cycles of reward and harm. Relationship scams frequently exploit trauma bonding mechanisms.

- Trauma-Related Dissociation — Trauma-related dissociation refers to dissociative responses linked to threat, betrayal, or chronic stress. It differs from everyday dissociation.

Author Biographies

-/ 30 /-

What do you think about this?

Please share your thoughts in a comment below!

2 Comments

Leave A Comment

Important Information for New Scam Victims

- Please visit www.ScamVictimsSupport.org – a SCARS Website for New Scam Victims & Sextortion Victims.

- SCARS Institute now offers its free, safe, and private Scam Survivor’s Support Community at www.SCARScommunity.org – this is not on a social media platform, it is our own safe & secure platform created by the SCARS Institute especially for scam victims & survivors.

- SCARS Institute now offers a free recovery learning program at www.SCARSeducation.org.

- Please visit www.ScamPsychology.org – to more fully understand the psychological concepts involved in scams and scam victim recovery.

If you are looking for local trauma counselors, please visit counseling.AgainstScams.org

If you need to speak with someone now, you can dial 988 or find phone numbers for crisis hotlines all around the world here: www.opencounseling.com/suicide-hotlines

Statement About Victim Blaming

Some of our articles discuss various aspects of victims. This is both about better understanding victims (the science of victimology) and their behaviors and psychology. This helps us to educate victims/survivors about why these crimes happened and not to blame themselves, better develop recovery programs, and help victims avoid scams in the future. At times, this may sound like blaming the victim, but it does not blame scam victims; we are simply explaining the hows and whys of the experience victims have.

These articles, about the Psychology of Scams or Victim Psychology – meaning that all humans have psychological or cognitive characteristics in common that can either be exploited or work against us – help us all to understand the unique challenges victims face before, during, and after scams, fraud, or cybercrimes. These sometimes talk about some of the vulnerabilities the scammers exploit. Victims rarely have control of them or are even aware of them, until something like a scam happens, and then they can learn how their mind works and how to overcome these mechanisms.

Articles like these help victims and others understand these processes and how to help prevent them from being exploited again or to help them recover more easily by understanding their post-scam behaviors. Learn more about the Psychology of Scams at www.ScamPsychology.org

SCARS INSTITUTE RESOURCES:

If You Have Been Victimized By A Scam Or Cybercrime

♦ If you are a victim of scams, go to www.ScamVictimsSupport.org for real knowledge and help

♦ SCARS Institute now offers its free, safe, and private Scam Survivor’s Support Community at www.SCARScommunity.org/register – this is not on a social media platform, it is our own safe & secure platform created by the SCARS Institute especially for scam victims & survivors.

♦ Enroll in SCARS Scam Survivor’s School now at www.SCARSeducation.org

♦ To report criminals, visit https://reporting.AgainstScams.org – we will NEVER give your data to money recovery companies like some do!

♦ Follow us and find our podcasts, webinars, and helpful videos on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@RomancescamsNowcom

♦ Learn about the Psychology of Scams at www.ScamPsychology.org

♦ Dig deeper into the reality of scams, fraud, and cybercrime at www.ScamsNOW.com and www.RomanceScamsNOW.com

♦ Scam Survivor’s Stories: www.ScamSurvivorStories.org

♦ For Scam Victim Advocates visit www.ScamVictimsAdvocates.org

♦ See more scammer photos on www.ScammerPhotos.com

You can also find the SCARS Institute’s knowledge and information on Facebook, Instagram, X, LinkedIn, and TruthSocial

Psychology Disclaimer:

All articles about psychology and the human brain on this website are for information & education only

The information provided in this and other SCARS articles are intended for educational and self-help purposes only and should not be construed as a substitute for professional therapy or counseling.

Note about Mindfulness: Mindfulness practices have the potential to create psychological distress for some individuals. Please consult a mental health professional or experienced meditation instructor for guidance should you encounter difficulties.

While any self-help techniques outlined herein may be beneficial for scam victims seeking to recover from their experience and move towards recovery, it is important to consult with a qualified mental health professional before initiating any course of action. Each individual’s experience and needs are unique, and what works for one person may not be suitable for another.

Additionally, any approach may not be appropriate for individuals with certain pre-existing mental health conditions or trauma histories. It is advisable to seek guidance from a licensed therapist or counselor who can provide personalized support, guidance, and treatment tailored to your specific needs.

If you are experiencing significant distress or emotional difficulties related to a scam or other traumatic event, please consult your doctor or mental health provider for appropriate care and support.

Also read our SCARS Institute Statement about Professional Care for Scam Victims – click here

If you are in crisis, feeling desperate, or in despair, please call 988 or your local crisis hotline – international numbers here.

More ScamsNOW.com Articles

A Question of Trust

At the SCARS Institute, we invite you to do your own research on the topics we speak about and publish. Our team investigates the subject being discussed, especially when it comes to understanding the scam victims-survivors’ experience. You can do Google searches, but in many cases, you will have to wade through scientific papers and studies. However, remember that biases and perspectives matter and influence the outcome. Regardless, we encourage you to explore these topics as thoroughly as you can for your own awareness.

![NavyLogo@4x-81[1] Protective Dissociation and Scam Victims - 2026](https://scamsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/NavyLogo@4x-811.png)

![scars-institute[1] Protective Dissociation and Scam Victims - 2026](https://scamsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/scars-institute1.png)

![niprc1.png1_-150×1501-1[1] Protective Dissociation and Scam Victims - 2026](https://scamsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/niprc1.png1_-150x1501-11.webp)

I find this article difficult to understand but interesting, and I need to read it several times to benefit from it. I’m also having a hard time identifying dissociation as it relates to my scam. In general, I remember experiencing protective dissociation at times and realize it’s to stop overwhelm but I can’t relate it to the scam.

This is not something that happened during the scam, it happens after the discovery and the onset of trauma.