The Life Story Project – A New View of Our Lives – A Non-Linear View

A TED Talk

Primary Category: Recovery Psychology

Author:

• Bruce Feiler, Writer, TV host, a leading voice on family, work, transitions, and meaning. His book, Life is in the Transitions: Mastering Change at Any Age, describes his journey across America, collecting hundreds of life stories, exploring how we can navigate life’s growing number of with skill and purpose.

The Life Story Project – A New View of Our Lives – A Non-Linear View

How do you navigate life’s growing number of transitions with meaning, purpose and skill? Writer Bruce Feiler offers a powerful way to handle uncertain, painful and confusing times — or “lifequakes”, as he calls them. Learn how to equip yourself with the essential tools and mindset to ride out (and rewrite) the toughest chapters of your life story, and turn unease and upheaval into growth and renewal.

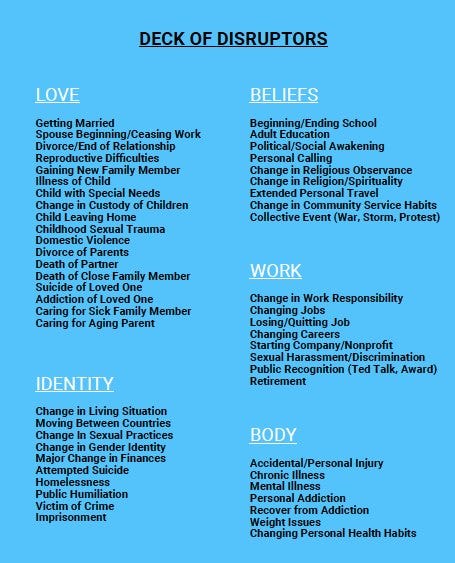

Learn more here: The Deck of Disruptors – by Bruce Feiler (substack.com)

TED Talk: Bruce Feiler: The secret to mastering life’s biggest transitions | TED Talk

TED Talk Video Transcript

“What we’ve learned from a generation of brain research is that story isn’t just part of you, it is you in a fundamental way. Life is the story we tell ourselves.”

For more information about this research, see here and here.

“…The five stages of grief. These are all linear constructs.”

Clarification: The five stages of grief model, documented by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in her 1969 monograph, was highly criticized for providing what was considered to be a linear construct of the grieving process. Although in 2005, Kübler-Ross tried to clarify that her stages were non-linear, and that people could experience these aspects of grief at different times and in no particular order, critics of her model continued to argue that it is not possible to have stages that universally represent people’s reaction to loss. For more details, see here.

-/ 30 /-

What do you think about this?

Please share your thoughts in a comment below!

Statement About Victim Blaming

SCARS Institute articles examine different aspects of the scam victim experience, as well as those who may have been secondary victims. This work focuses on understanding victimization through the science of victimology, including common psychological and behavioral responses. The purpose is to help victims and survivors understand why these crimes occurred, reduce shame and self-blame, strengthen recovery programs and victim opportunities, and lower the risk of future victimization.

At times, these discussions may sound uncomfortable, overwhelming, or may be mistaken for blame. They are not. Scam victims are never blamed. Our goal is to explain the mechanisms of deception and the human responses that scammers exploit, and the processes that occur after the scam ends, so victims can better understand what happened to them and why it felt convincing at the time, and what the path looks like going forward.

Articles that address the psychology, neurology, physiology, and other characteristics of scams and the victim experience recognize that all people share cognitive and emotional traits that can be manipulated under the right conditions. These characteristics are not flaws. They are normal human functions that criminals deliberately exploit. Victims typically have little awareness of these mechanisms while a scam is unfolding and a very limited ability to control them. Awareness often comes only after the harm has occurred.

By explaining these processes, these articles help victims make sense of their experiences, understand common post-scam reactions, and identify ways to protect themselves moving forward. This knowledge supports recovery by replacing confusion and self-blame with clarity, context, and self-compassion.

Additional educational material on these topics is available at ScamPsychology.org – ScamsNOW.com and other SCARS Institute websites.

-/ 30 /-

What do you think about this?

Please share your thoughts in a comment below!

2 Comments

Leave A Comment

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CATEGORIES

![NavyLogo@4x-81[1] The Life Story Project - A New View of Our Lives - A Non-Linear View - A TED Talk by Bruce Feiler - 2024](https://scamsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/NavyLogo@4x-811.png)

ARTICLE META

Important Information for New Scam Victims

- Please visit www.ScamVictimsSupport.org – a SCARS Website for New Scam Victims & Sextortion Victims.

- SCARS Institute now offers its free, safe, and private Scam Survivor’s Support Community at www.SCARScommunity.org – this is not on a social media platform, it is our own safe & secure platform created by the SCARS Institute especially for scam victims & survivors.

- SCARS Institute now offers a free recovery learning program at www.SCARSeducation.org.

- Please visit www.ScamPsychology.org – to more fully understand the psychological concepts involved in scams and scam victim recovery.

If you are looking for local trauma counselors, please visit counseling.AgainstScams.org

If you need to speak with someone now, you can dial 988 or find phone numbers for crisis hotlines all around the world here: www.opencounseling.com/suicide-hotlines

Statement About Victim Blaming

Some of our articles discuss various aspects of victims. This is both about better understanding victims (the science of victimology) and their behaviors and psychology. This helps us to educate victims/survivors about why these crimes happened and not to blame themselves, better develop recovery programs, and help victims avoid scams in the future. At times, this may sound like blaming the victim, but it does not blame scam victims; we are simply explaining the hows and whys of the experience victims have.

These articles, about the Psychology of Scams or Victim Psychology – meaning that all humans have psychological or cognitive characteristics in common that can either be exploited or work against us – help us all to understand the unique challenges victims face before, during, and after scams, fraud, or cybercrimes. These sometimes talk about some of the vulnerabilities the scammers exploit. Victims rarely have control of them or are even aware of them, until something like a scam happens, and then they can learn how their mind works and how to overcome these mechanisms.

Articles like these help victims and others understand these processes and how to help prevent them from being exploited again or to help them recover more easily by understanding their post-scam behaviors. Learn more about the Psychology of Scams at www.ScamPsychology.org

SCARS INSTITUTE RESOURCES:

If You Have Been Victimized By A Scam Or Cybercrime

♦ If you are a victim of scams, go to www.ScamVictimsSupport.org for real knowledge and help

♦ SCARS Institute now offers its free, safe, and private Scam Survivor’s Support Community at www.SCARScommunity.org/register – this is not on a social media platform, it is our own safe & secure platform created by the SCARS Institute especially for scam victims & survivors.

♦ Enroll in SCARS Scam Survivor’s School now at www.SCARSeducation.org

♦ To report criminals, visit https://reporting.AgainstScams.org – we will NEVER give your data to money recovery companies like some do!

♦ Follow us and find our podcasts, webinars, and helpful videos on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@RomancescamsNowcom

♦ Learn about the Psychology of Scams at www.ScamPsychology.org

♦ Dig deeper into the reality of scams, fraud, and cybercrime at www.ScamsNOW.com and www.RomanceScamsNOW.com

♦ Scam Survivor’s Stories: www.ScamSurvivorStories.org

♦ For Scam Victim Advocates visit www.ScamVictimsAdvocates.org

♦ See more scammer photos on www.ScammerPhotos.com

You can also find the SCARS Institute’s knowledge and information on Facebook, Instagram, X, LinkedIn, and TruthSocial

Psychology Disclaimer:

All articles about psychology and the human brain on this website are for information & education only

The information provided in this and other SCARS articles are intended for educational and self-help purposes only and should not be construed as a substitute for professional therapy or counseling.

Note about Mindfulness: Mindfulness practices have the potential to create psychological distress for some individuals. Please consult a mental health professional or experienced meditation instructor for guidance should you encounter difficulties.

While any self-help techniques outlined herein may be beneficial for scam victims seeking to recover from their experience and move towards recovery, it is important to consult with a qualified mental health professional before initiating any course of action. Each individual’s experience and needs are unique, and what works for one person may not be suitable for another.

Additionally, any approach may not be appropriate for individuals with certain pre-existing mental health conditions or trauma histories. It is advisable to seek guidance from a licensed therapist or counselor who can provide personalized support, guidance, and treatment tailored to your specific needs.

If you are experiencing significant distress or emotional difficulties related to a scam or other traumatic event, please consult your doctor or mental health provider for appropriate care and support.

Also read our SCARS Institute Statement about Professional Care for Scam Victims – click here

If you are in crisis, feeling desperate, or in despair, please call 988 or your local crisis hotline – international numbers here.

More ScamsNOW.com Articles

A Question of Trust

At the SCARS Institute, we invite you to do your own research on the topics we speak about and publish. Our team investigates the subject being discussed, especially when it comes to understanding the scam victims-survivors’ experience. You can do Google searches, but in many cases, you will have to wade through scientific papers and studies. However, remember that biases and perspectives matter and influence the outcome. Regardless, we encourage you to explore these topics as thoroughly as you can for your own awareness.

![scars-institute[1] The Life Story Project - A New View of Our Lives - A Non-Linear View - A TED Talk by Bruce Feiler - 2024](https://scamsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/scars-institute1.png)

![niprc1.png1_-150×1501-1[1] The Life Story Project - A New View of Our Lives - A Non-Linear View - A TED Talk by Bruce Feiler - 2024](https://scamsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/niprc1.png1_-150x1501-11.webp)

I often think to my “I’m going through some things right now but it will get better”. I look forward to the future and moving on from the messy middle.

É realmente verdade que as vidas lineares acabaram, tudo é incerto: o emprego, casamento…, ou seja, ela é cheia de altos e baixos, dos quais podemos ou não ser responsáveis. O que é importante ressalvar é que das nossas contingências não acabemos sós.