Human Trafficking & Scam Slavery – UN Issues New Report

By United Nations and SCARS Editorial Team

UN Report: Scam Slavery Is A Form Of Human Trafficking In Which People Are Forced To Work In Scam Call Centers

SCARS Overview

The victims are often lured with promises of good jobs and high salaries, but once they arrive at the call center, they are forced to work long hours under abusive conditions. They are also often threatened with violence or deportation if they try to escape.

Southeast Asia is a major hub for scam slavery. The region is home to a large number of poor and unemployed people who are vulnerable to exploitation. The perpetrators of scam slavery often target these people with promises of easy money.

Human trafficking for scam-related organized crime in Southeast Asia:

- Southeast Asia is a major hub for human trafficking, and the region is increasingly being used as a base for cybercrime operations.

- Criminal gangs use a variety of methods to traffic people into scam centers, including deception, coercion, and force.

- Victims of human trafficking in scam centers are often subjected to long hours of work, threats, and physical abuse.

- The scam industry in Southeast Asia is estimated to generate billions of dollars in profits each year.

Some of the most common types of scams that are perpetrated by human trafficking victims in Southeast Asia include:

- Romance scams: Victims are contacted online by someone who claims to be interested in a romantic relationship. The scammer eventually asks for money or personal information, which is then used to commit fraud.

- Investment scams: Victims are promised high returns on investments that are either non-existent or highly risky.

- Tech support scams: Victims are contacted by someone who claims to be from a tech company and says that their computer has been infected with a virus. The victim is then tricked into giving the scammer remote access to their computer, which is then used to steal personal information or install malware.

From the UN Report

UN Report: Introduction

This briefing paper sets out human rights concerns arising since early 2021 from online scam operations including their link to human trafficking in Southeast Asia as well as recommendations drawn from international human rights standards.

These concerns occur in the context of wide-ranging digital criminal activity such as romance-investment scams, crypto fraud, money laundering and illegal gambling. At the time of writing this paper, the situation remains fluid: hundreds of thousands of people from across the region and beyond have been forcibly engaged in online criminality, States within the region are trying to identify actions and policies to address this phenomenon, while criminal actors are reacting by finding ways to change and relocate their operations, building new centres across the region and upgrading existing compounds.

At the outset it is important to acknowledge that there are two sets of victims in this complex phenomenon. People who have been defrauded through online criminality are victims of the financial and other crimes committed by these scam operations. Many have lost their life savings, taken on debt and suffered shame and stigma for having been scammed. On the other side, individuals who are coerced into working in these scam operations and endure inhumane treatment are victims of serious human rights violations and it is their situation that is the focus of this briefing paper.

People who are forced to take part in online scams are most often trafficked persons and migrants in vulnerable situations who face a range of human rights risks, violations and abuses. A human rights-based approach to this complex situation means not merely addressing organised crime or enforcing border controls, but seeks to place the victims at the centre of the response, by addressing structural factors, tackling impunity and providing protection and justice for victims of trafficking and migrants in situations of vulnerability. Human trafficking is a recognised criminal offence under international law and many of the practices associated with trafficking constitute violations under international human rights law.

Violations of human rights are both a root cause of trafficking and can occur throughout the trafficking cycle. The majority of people trafficked into online scam operations are men, although women and children are also among the victims. Most are not citizens of the countries in which the trafficking occurs, however reports have indicated that at least in some countries nationals are also being targeted.

People who have been trafficked into online forced criminality face threats to their right to life, liberty and security of the person. They are subject to torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment, arbitrary detention, sexual violence, forced labour and other forms of labour exploitation as well as a range of other human rights violations and abuses This briefing paper is primarily focused on migrants who have

endured trafficking and other human rights violations in the context of the scam operations, while acknowledging that the concerns and guidance contained here apply equally in most cases to citizens in this situation.The information in this briefing paper draws on primary and secondary research by the UN Human Rights Office, including victim testimony, as well as the work of the UN human rights mechanisms and information from other UN entities, supplemented by open-source information. While not exhaustive, Section A seeks to draw attention to the many serious human rights issues that result from this emerging phenomenon. Section B offers guidance to States and other stakeholders drawing from human rights standards and offers targeted recommendations aimed at ensuring responses are human rights-based. The briefing paper was transmitted to the relevant States for factual comments prior to publication.

UN Report: History and background

Online scam operations are rooted in the rise of casinos and online gambling operations in the Southeast Asian region.

Gambling, particularly online gambling, is officially banned to varying extents in China, Cambodia, Thailand and Lao PDR. There have been different efforts since 2016 to close down such operations in the region, but in many cases these attempts merely caused them to move their location and to adapt, often increasing the influence of organised criminal groups. Between 2014 to 2019, for example, the number of casinos in Cambodia increased by 163 per cent: from 57 in 2014 to 150 in 2019. The Philippine offshore gambling operator (POGO) system was created in 2016 to facilitate online gaming exclusively for players outside the Philippines, employing tens of thousands of migrant workers as well as a smaller number of Filipinos.

There has been concern about criminal activities linked to these operations, particularly cases of kidnapping and illegal detention of employees. Scams aimed at defrauding people also have a long history in the region; organised criminal groups have been running scam operations out of Cambodia for over a decade, with a sharp increase seen since 2016. In Myanmar, organised crime actors have operated in the country for years but the

situation, especially related to trafficking into these scam operations, is reported to have worsened since the military coup in February 2021.The COVID-19 pandemic and associated response measures had a drastic impact on such illicit activities across the region. Public health measures closed casinos in many countries and in response, casino operators moved operations to less regulated territories as well as to the increasingly lucrative online space. Faced with new operational realities, criminal gangs increasingly targeted migrant workers, who were stranded in these countries and were out of work due to border and business closures, to work in the scam centres. At the same time, the pandemic response measures saw millions of people restricted to their homes and spending more time online, making them ready targets for this online fraud. As countries in the region opened up from the pandemic response measures in the course of 2021-22, traffickers continued to exploit the economic distress that had resulted from the pandemic and the needs of many to find alternative livelihoods.

Taking advantage of the lack of decent work opportunities in many countries, the business shutdowns during the pandemic, lack of social protection, and in particular, the reduced job opportunities for young graduates, traffickers were easily able to fraudulently recruit people into criminal operations under the pretence of offering them real jobs.

Digital platforms greatly expanded the reach of organised criminal actors engaged in online fraud, enabling them to target for recruitment people in different countries and from different language groups. For example, the growth in online gambling in Viet Nam has created a demand for Vietnamese speakers to service the market. It is important to note that while the online scam industry has considerably increased since the start of the pandemic, many of Southeast Asia’s casino towns were already implicated in human rights abuses such as human trafficking and child sexual exploitation.

Scamming is a profitable industry worldwide; according to one report, revenue in 2021 from scamming globally amounted to USD 7.8 billion worth of stolen cryptocurrency. In Southeast Asia reports suggest that scam centres generate revenue amounting to billions of US dollars. The number of people who have fallen victim to online scam trafficking in Southeast Asia is difficult to estimate because of its clandestine nature and gaps in the official response. Credible sources indicate that at least 120,000 people across Myanmar may be held in situations where they are forced to carry out

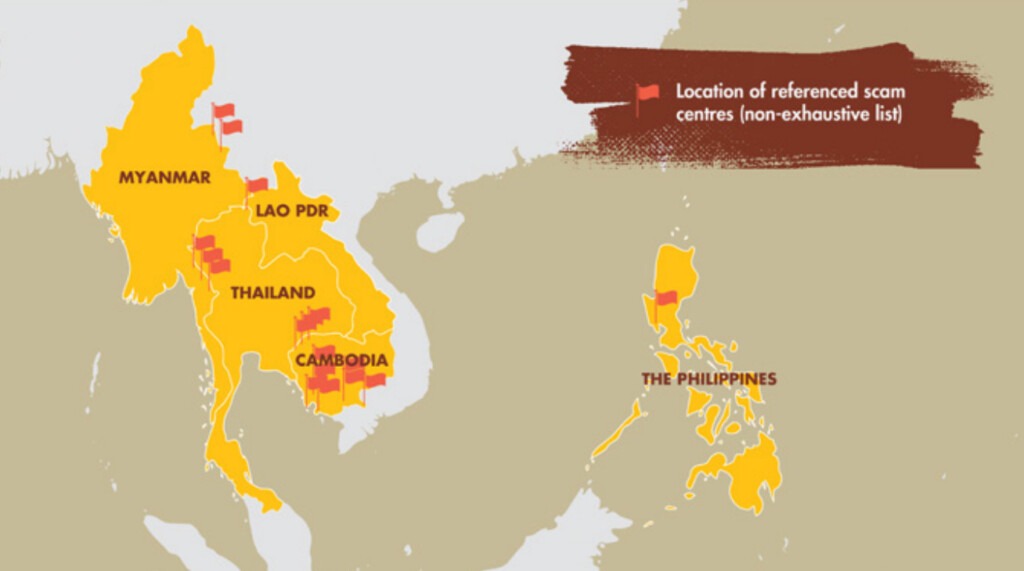

online scams, while credible estimates in Cambodia have similarly indicated at least 100,000 people forcibly involved in online scams.In Cambodia as of July 2023, online scam centres are or were reportedly operating in Phnom Penh, Kandal, Pursat, Koh Kong, Bavet, Preah Sihanouk, Oddar Meanchey, Svay Rieng, including within the Dara Sakor SEZ and Henge Thmorda SEZ.

In Myanmar centres are allegedly located in Shwe Kokko and other locations in Myawaddy on the Thai border including KK Zone and other compounds along the Moei River, Kokang Self-Administered Zone in Shan State and the Wa-administered city of Mong La on the Chinese border among others. In Lao PDR the industry is said to be centred around the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in the northwest of the country.

In the Philippines, scam centres are reportedly operating within some POGOs and in SEZs such as the Clark Free Port Zone: the country has over 30 licensed POGOs, with more operating illegally in the country.

UN Report: Changing profiles

Documented trafficking cases in Southeast Asia have usually involved people who have had limited access to education and are engaged in low-wage work. However, the profile of people trafficked into these recent online scam operations is different; many of the victims are well-educated, sometimes coming from professional jobs or with graduate or even post-graduate degrees, computer-literate and multi-lingual. Victims have come from across the ASEAN region (from Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam), China (including Hong Kong, Taiwan), as well as countries in South Asia (Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan), East Africa (Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania), Egypt, Turkey and also Brazil. Men make up the majority of the victims, although women have also been targeted and, while most of the victims are adults, reports indicate the presence of adolescent victims.

Notwithstanding that all countries in the region have a long history of engaging in counter-trafficking responses, countries like Cambodia, Lao PDR and Myanmar – in which these online scam operations have been documented to be taking place – have seen their position shift from countries of origin of trafficked persons to the destination countries into which people from other countries are trafficked.

Understanding the consequences of and adapting to this new situation has been a challenge. This shift has also taken place in the context of a region where migration corridors are multifaceted. Long and porous land borders between the countries of mainland Southeast Asia have facilitated various types of mobility, in many cases through irregular channels, with people on the move often using the services of smugglers and other intermediaries where regular migration pathways are found to be expensive and difficult to access. Thailand is increasingly a transit country for these operations. People travel into Thailand before being moved by their traffickers over the border to a neighbouring State, while in other contexts trafficked persons transit through Thailand as they are moved from one scam operation to another (for example, citizens of Viet Nam were first trafficked into Myanmar and from there re-trafficked to Cambodia via Thailand).

The visa-free entry of ASEAN nationals within the ASEAN region has also complicated the practical ability of authorities in destination countries to identify nationals of other ASEAN countries as victims of trafficking, with border personnel in these countries often being unfamiliar with protection screening in relation to the entry and stay of ASEAN nationals.

Recommendations on promoting and protecting human rights

States, and other relevant actors as applicable, should:

- Address the factors that create or increase situations of vulnerability that put individuals at risk of trafficking and other human rights violations, including inequality, poverty, lack of decent work opportunities, all forms of discrimination as well as restrictive migration governance measures, and take legislative, policy and other rights-based measures to end these criminal operations and their exploitative practices.

- Ensure an adequate legal framework on trafficking by amending or adopting legislation in accordance with international standards to ensure, inter alia, that the crime of trafficking, and practices covered by its definition, are precisely defined in national law and the human rights protection of trafficked persons is effectively built into anti-trafficking legislation.

- Review and amend any laws and policies that may have unintended negative human rights consequences for victims of trafficking or other migrants in vulnerable situations, including in the context of counter-trafficking or border control measures.

- Ensure that business enterprises, including in conflict areas, whether private or State-owned/supported, are not involved in trafficking in persons, including for the purpose of labour exploitation or forced criminality, and ensure transparent and strict requirements for the entire recruitment process and strict rules for placement and employment agencies.

- Enforce applicable legislation and regulations to ensure that all businesses, including those operating in SEZs, respect human rights throughout their operations and effectively address the risk of business involvement in human rights abuses.

- Provide law enforcement personnel with adequate training in the investigation and prosecution of cases of trafficking that is human rights-based and sensitive to the needs of trafficked persons, including in conducting joint investigations and through common prosecution methodologies where relevant; as well as facilitate the safe involvement of victims in prosecution.

- Respect and support the activities of journalists and other human rights defenders including National Human Rights Institutions and civil society organizations and provide, in law and in practice, a safe, accessible and enabling environment for their work and ensure that they are protected from violence, retaliation and other kinds of pressure or arbitrary action by State or non-State actors as a consequence of their work.

UN Report: Online Scam Operations And Trafficking Into Forced Criminality In Southeast Asia: Recommendations For A Human Rights Response

SCARS Resources:

- For New Victims of Relationship Scams newvictim.AgainstScams.org

- Subscribe to SCARS Newsletter newsletter.againstscams.org

- Sign up for SCARS professional support & recovery groups, visit support.AgainstScams.org

- Find competent trauma counselors or therapists, visit counseling.AgainstScams.org

- Become a SCARS Member and get free counseling benefits, visit membership.AgainstScams.org

- Report each and every crime, learn how to at reporting.AgainstScams.org

- Learn more about Scams & Scammers at RomanceScamsNOW.com and ScamsNOW.com

- Global Cyber Alliance ACT Cybersecurity Tool Website: Actionable Cybersecurity Tools (ACT) (globalcyberalliance.org)

- Self-Help Books for Scam Victims are at shop.AgainstScams.org

- Donate to SCARS and help us help others at donate.AgainstScams.org

- Worldwide Crisis Hotlines: International Suicide Hotlines – OpenCounseling : OpenCounseling

- Campaign To End Scam Victim Blaming – 2024 (scamsnow.com)

More:

- Scam Syndicates in Southeast Asia – Guest Editorial (romancescamsnow.com)

- The New World Order – Scamming in Southeast Asia (romancescamsnow.com)

- Coming In Contact With Forced Labor Scammer Slaves (scamsnow.com)

- 2,700 Scam Slaves Rescued In The Philippines [VIDEO] (scamsnow.com)

- Human Scam Trafficking – The Knoble Report (scamsnow.com)

- INTERPOL Issues Global Warning On Human Trafficking-Fueled Fraud (scamsnow.com)

- Scam Slavery In Southeast Asia (romancescamsnow.com)

- Sha Zhu Pan 殺主盤 Pig Butchering Romance/Investment Scams – Overview (romancescamsnow.com)

- ASEAN anti-cybercrime declaration calls for united front (romancescamsnow.com)

More ScamsNOW.com Articles

-/ 30 /-

What do you think about this?

Please share your thoughts in a comment below!

SCARS LINKS: AgainstScams.org RomanceScamsNOW.com ContraEstafas.org ScammerPhotos.com Anyscam.com ScamsNOW.com

reporting.AgainstScams.org support.AgainstScams.org membership.AgainstScams.org donate.AgainstScams.org shop.AgainstScams.org

youtube.AgainstScams.org linkedin.AgainstScams.org facebook.AgainstScams.org

Important Information for New Scam Victims

- Please visit www.ScamVictimsSupport.org – a SCARS Website for New Scam Victims & Sextortion Victims.

- SCARS Institute now offers its free, safe, and private Scam Survivor’s Support Community at www.SCARScommunity.org – this is not on a social media platform, it is our own safe & secure platform created by the SCARS Institute especially for scam victims & survivors.

- SCARS Institute now offers a free recovery learning program at www.SCARSeducation.org.

- Please visit www.ScamPsychology.org – to more fully understand the psychological concepts involved in scams and scam victim recovery.

If you are looking for local trauma counselors, please visit counseling.AgainstScams.org

If you need to speak with someone now, you can dial 988 or find phone numbers for crisis hotlines all around the world here: www.opencounseling.com/suicide-hotlines

Statement About Victim Blaming

Some of our articles discuss various aspects of victims. This is both about better understanding victims (the science of victimology) and their behaviors and psychology. This helps us to educate victims/survivors about why these crimes happened and not to blame themselves, better develop recovery programs, and help victims avoid scams in the future. At times, this may sound like blaming the victim, but it does not blame scam victims; we are simply explaining the hows and whys of the experience victims have.

These articles, about the Psychology of Scams or Victim Psychology – meaning that all humans have psychological or cognitive characteristics in common that can either be exploited or work against us – help us all to understand the unique challenges victims face before, during, and after scams, fraud, or cybercrimes. These sometimes talk about some of the vulnerabilities the scammers exploit. Victims rarely have control of them or are even aware of them, until something like a scam happens, and then they can learn how their mind works and how to overcome these mechanisms.

Articles like these help victims and others understand these processes and how to help prevent them from being exploited again or to help them recover more easily by understanding their post-scam behaviors. Learn more about the Psychology of Scams at www.ScamPsychology.org

SCARS INSTITUTE RESOURCES:

If You Have Been Victimized By A Scam Or Cybercrime

♦ If you are a victim of scams, go to www.ScamVictimsSupport.org for real knowledge and help

♦ SCARS Institute now offers its free, safe, and private Scam Survivor’s Support Community at www.SCARScommunity.org/register – this is not on a social media platform, it is our own safe & secure platform created by the SCARS Institute especially for scam victims & survivors.

♦ Enroll in SCARS Scam Survivor’s School now at www.SCARSeducation.org

♦ To report criminals, visit https://reporting.AgainstScams.org – we will NEVER give your data to money recovery companies like some do!

♦ Follow us and find our podcasts, webinars, and helpful videos on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@RomancescamsNowcom

♦ Learn about the Psychology of Scams at www.ScamPsychology.org

♦ Dig deeper into the reality of scams, fraud, and cybercrime at www.ScamsNOW.com and www.RomanceScamsNOW.com

♦ Scam Survivor’s Stories: www.ScamSurvivorStories.org

♦ For Scam Victim Advocates visit www.ScamVictimsAdvocates.org

♦ See more scammer photos on www.ScammerPhotos.com

You can also find the SCARS Institute’s knowledge and information on Facebook, Instagram, X, LinkedIn, and TruthSocial

Psychology Disclaimer:

All articles about psychology and the human brain on this website are for information & education only

The information provided in this and other SCARS articles are intended for educational and self-help purposes only and should not be construed as a substitute for professional therapy or counseling.

Note about Mindfulness: Mindfulness practices have the potential to create psychological distress for some individuals. Please consult a mental health professional or experienced meditation instructor for guidance should you encounter difficulties.

While any self-help techniques outlined herein may be beneficial for scam victims seeking to recover from their experience and move towards recovery, it is important to consult with a qualified mental health professional before initiating any course of action. Each individual’s experience and needs are unique, and what works for one person may not be suitable for another.

Additionally, any approach may not be appropriate for individuals with certain pre-existing mental health conditions or trauma histories. It is advisable to seek guidance from a licensed therapist or counselor who can provide personalized support, guidance, and treatment tailored to your specific needs.

If you are experiencing significant distress or emotional difficulties related to a scam or other traumatic event, please consult your doctor or mental health provider for appropriate care and support.

Also read our SCARS Institute Statement about Professional Care for Scam Victims – click here

If you are in crisis, feeling desperate, or in despair, please call 988 or your local crisis hotline – international numbers here.

More ScamsNOW.com Articles

A Question of Trust

At the SCARS Institute, we invite you to do your own research on the topics we speak about and publish. Our team investigates the subject being discussed, especially when it comes to understanding the scam victims-survivors’ experience. You can do Google searches, but in many cases, you will have to wade through scientific papers and studies. However, remember that biases and perspectives matter and influence the outcome. Regardless, we encourage you to explore these topics as thoroughly as you can for your own awareness.

![NavyLogo@4x-81[1] Human Trafficking & Scam Slavery - UN Issues New Report](https://scamsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/NavyLogo@4x-811.png)

![scars-institute[1] Human Trafficking & Scam Slavery - UN Issues New Report](https://scamsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/scars-institute1.png)

![niprc1.png1_-150×1501-1[1] Human Trafficking & Scam Slavery - UN Issues New Report](https://scamsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/niprc1.png1_-150x1501-11.webp)