Schemas Part 4: SCARS Institute Schema Conflict Theory Resulting in Psychological Trauma

Exploring the Connection Between Schema Conflicts and the Experience of Psychological Trauma

Primary Category: Psychology of Scams

Authors:

• Tim McGuinness, Ph.D. – Anthropologist, Scientist, Director of the Society of Citizens Against Relationship Scams Inc.

• Vianey Gonzalez B.Sc(Psych) – Licensed Psychologist, Specialty in Crime Victim Trauma Therapy, Neuropsychologist, Certified Deception Professional, Psychology Advisory Panel & Director of the Society of Citizens Against Relationship Scams Inc.

About This Article

When a person’s core beliefs, or schemas, are confronted with conflicting experiences, it can significantly disrupt their psychological equilibrium and result in trauma.

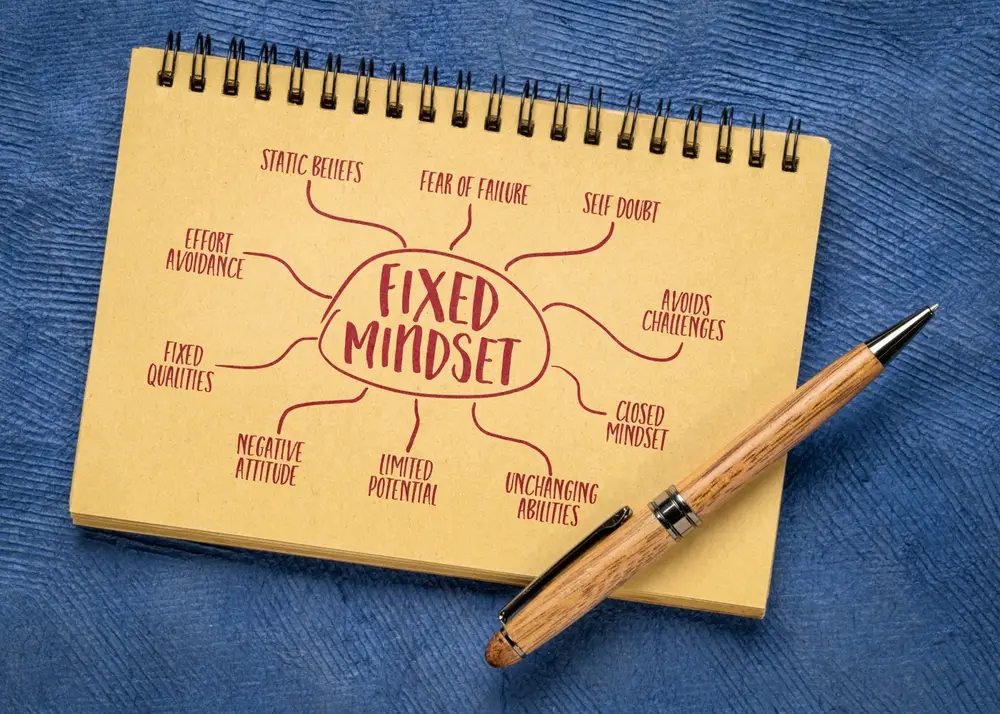

Schemas are deeply ingrained mental models that help individuals process the world based on past experiences. When a scam victim’s schema (such as trust in others or belief in financial security) is shattered, they experience cognitive dissonance and emotional distress.

The severity of the trauma depends on their ability to reconcile the conflicting experience with their mental framework. If they cannot resolve the disparity, it leads to heightened emotional turmoil, difficulty trusting others, and lasting psychological impacts.

Recognizing and understanding this schema conflict is key to managing trauma and fostering personal recovery.

SCARS Institute Schema Conflict Theory Resulting in Psychological Trauma in Scam Victims

Introduction

Schemas or Mental Models are the internal representations of how we understand and interact with the world around us.

These mental models are not exact mirrors of reality but rather simplified frameworks formed from our accumulated experiences, observations, and interpretations. These mental models can be accurate or distorted, based on true or false information, and they shape how we see other people and situations.

For scam victims, these mental models play a significant role at both the beginning of the scam and during the scam, concealing the scammer’s true intentions and making it difficult to see the truth. After the scam, these mental models can even hinder the recovery process by preventing victims from accepting help.

Schema modes are defined as the emotional states and behavioural coping responses activated when a traumatic memory is triggered (Johnston et al., 2009). Studies suggest that the schema modes theory could be suitable for exploring the emotions and behavioural states resulting from a traumatic experience.

The Relationship Between Schemas and Trauma

the relationship between someone’s schema and an experience that conflicts with it can be a significant underlying cause of psychological trauma. Schemas are deeply ingrained mental frameworks that help people make sense of the world based on their previous experiences, beliefs, and expectations. When an experience occurs that is in direct opposition to these mental models, it can lead to intense psychological distress, cognitive dissonance, and even trauma.

How this conflict leads to trauma:

Cognitive Dissonance

When an experience conflicts with an individual’s established schema, it creates a state of cognitive dissonance, where the person’s beliefs or expectations are contradicted by reality. For example, if someone has a schema that the world is a safe and predictable place, experiencing violence or betrayal can cause their entire worldview to collapse, leading to confusion and distress. This dissonance is difficult for the brain to reconcile, potentially leading to long-term emotional and psychological impacts. More below.

Shattered Assumptions

The shattered assumptions theory of trauma, proposed by Janoff-Bulman (1992), explains how trauma occurs when core beliefs (schemas) about the world, other people, and the self are challenged. For instance, individuals who hold the assumption that “bad things don’t happen to good people” may experience trauma when they face an unexpected betrayal, accident, or abuse. Their schema about fairness and safety is violated, which can be difficult to integrate into their existing understanding of the world. More below.

Emotional Dysregulation

When a schema is violated, it can trigger intense emotional responses, such as fear, helplessness, or anger. These emotions may overwhelm an individual’s ability to cope, leading to traumatic stress. For example, someone who believes that people are generally trustworthy may experience extreme distress when they are deceived or betrayed, leading to emotional dysregulation and long-term trauma responses such as hypervigilance, avoidance, or intrusive thoughts. More below.

Neurobiological Impact

Schemas also affect the way the brain processes and stores traumatic events. When trauma occurs, areas of the brain like the amygdala (responsible for emotional reactions) and the hippocampus (involved in memory formation) become highly active, especially when the trauma conflicts with pre-existing mental models. The brain’s inability to integrate the traumatic experience with existing schemas can lead to difficulties in processing and consolidating the memory, which is why trauma survivors may experience flashbacks, dissociation, or intrusive memories. More below.

Protective Maladaptive Schemas

In response to a traumatic event, individuals might develop maladaptive schemas to protect themselves from future harm. For instance, after experiencing betrayal, a person might develop a schema that “nobody can be trusted.” While this new schema is designed to prevent future hurt, it can also lead to emotional isolation, hypervigilance, and difficulties in forming healthy relationships, perpetuating trauma. More below.

Schema Conflict Results in Cognitive Dissonance and Trauma in Scam Victims

Cognitive dissonance plays a central role in the trauma experienced by scam victims, particularly in cases of romance or financial fraud. Cognitive dissonance refers to the psychological discomfort that arises when a person holds two or more contradictory beliefs, values, or perceptions. In the context of scam victims, this dissonance occurs when the trust and positive expectations they had toward the scammer clash with the reality of being deceived and manipulated.

Here’s how cognitive dissonance contributes to trauma in scam victims:

Contradiction Between Perception and Reality

Scam victims typically believe they are engaging in genuine relationships or financial opportunities. Their mental models or schemas are built around trust, honesty, and mutual benefit. When they discover that the person or opportunity they trusted is a fraud, the stark contradiction between their belief (that they were in a legitimate relationship or investment) and the reality (that they were exploited) creates significant cognitive dissonance. This internal conflict can cause intense emotional distress, confusion, and self-doubt.

Self-Blame and Guilt

Many scam victims struggle with feelings of self-blame as a result of cognitive dissonance. They may ask themselves, “How could I have been so naïve?” or “Why didn’t I see the signs earlier?” These thoughts arise because their schemas, or mental models, of being rational, intelligent individuals are challenged by the realization that they were manipulated. This blame and guilt contribute to their trauma, as they begin to question their judgment, trust in others, and sense of self-worth.

Emotional Bond and Betrayal

In romance scams in particular, victims often form deep emotional connections with the scammer, further complicating their cognitive dissonance. They invested emotionally, and often financially, believing they were helping someone they loved or cared for. When the scam is revealed, they must reconcile the positive emotions they felt with the harsh reality of betrayal. This emotional betrayal intensifies the trauma, as the victim not only loses financial stability but also grapples with the destruction of a meaningful relationship they believed was real.

Delayed Recognition and Escalation

Cognitive dissonance often leads scam victims to rationalize inconsistencies in the scammer’s behavior or requests, prolonging their entrapment. The human brain naturally seeks to reduce the discomfort caused by dissonance, and victims may engage in rationalization or denial to preserve their existing beliefs about the scammer. For example, when faced with odd requests for money or evasive behavior, they might attribute it to circumstances beyond the scammer’s control, like an emergency or technical issue. This delay in recognizing the scam increases the eventual shock and trauma once the truth is revealed.

Impact on Recovery

Even after the scam is uncovered, cognitive dissonance continues to impact the recovery process. Victims often experience difficulty accepting the extent of the deception, and the emotional aftermath may include denial, shame, and avoidance of help. Cognitive dissonance makes it hard for them to trust others, even those offering genuine support because their previous trust was so deeply violated. This can hinder their ability to seek professional help or lean on their social networks, prolonging their recovery from the trauma.

Trauma and Mental Health

The unresolved cognitive dissonance can lead to prolonged trauma-related mental health issues, such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety. Scam victims may replay the events repeatedly in their minds, trying to reconcile the dissonance and understand how they were deceived. This mental replaying, coupled with self-blame and a distorted sense of trust, often exacerbates the trauma, making it harder to heal and move forward.

Restoring Cognitive Balance

Recovery from cognitive dissonance requires victims to realign their mental models with reality. This process often involves therapy, where victims are guided to challenge the irrational beliefs they held about the scammer and the situation. By learning to accept that they were manipulated by a professional scammer—rather than blaming themselves—they can reduce the dissonance and gradually rebuild their sense of trust and self-worth.

In summary, cognitive dissonance significantly contributes to the emotional and psychological trauma experienced by scam victims. The internal conflict between their beliefs and the harsh reality of deception leads to distress, self-blame, and difficulty in accepting help, all of which can prolong the recovery process. Recognizing and addressing cognitive dissonance is a key step in overcoming the trauma of being scammed.

Shattered Assumptions and Their Role in Scam Victims’ Trauma

The theory of “shattered assumptions,” developed by psychologist Ronnie Janoff-Bulman, suggests that people hold fundamental beliefs about the world, others, and themselves that help them feel safe, secure, and in control. These assumptions often include beliefs like: “the world is a generally safe place,” “good things happen to good people,” and “I can trust my judgment.” When these core assumptions are challenged or destroyed by a traumatic event—such as falling victim to a scam—psychological distress and trauma are likely to follow.

In scam victims, the breakdown of these basic beliefs intensifies the emotional and psychological impact of the scam, leading to feelings of betrayal, disillusionment, and helplessness.

Assumptions About Trust and Honesty

One of the most significant assumptions that scam victims hold is that people, especially those with whom they form close bonds (e.g., in romance scams), are inherently trustworthy and honest. Scammers exploit these beliefs, creating fake personas and emotional bonds to manipulate their victims. When the scam is revealed, the victim’s fundamental belief in trust and honesty is shattered. This leads to a profound sense of betrayal, often equated with emotional violence, as the victim realizes that the person they confided in and cared for never existed. This breach of trust can leave lasting scars, making it difficult for victims to trust others again, even in future genuine relationships.

Assumptions About Personal Judgment and Competence

Scam victims often hold the belief that they are capable of making sound judgments about people and situations. However, after realizing they have been manipulated, this assumption is shattered. Victims frequently ask themselves, “How could I have been so foolish?” or “Why didn’t I see the signs?” This self-doubt erodes their confidence in their ability to make decisions and discern between truth and deception. This loss of confidence can contribute to lasting trauma, as victims may feel incompetent or powerless in navigating future relationships, whether personal or financial. This internalized sense of failure fuels feelings of shame and guilt, which further complicate recovery.

Assumptions About Justice and Fairness

Another core belief that is shattered in scam victims is the assumption that the world is a just and fair place, where good behavior is rewarded, and wrongdoers are punished. Scammers exploit this belief by manipulating victims into thinking they are part of a genuine, beneficial transaction or relationship. When the scam is uncovered, victims must confront the reality that not only were they deceived, but the scammer may never face justice, and their losses may never be recovered. This realization contributes to a sense of powerlessness and injustice, amplifying their emotional distress. Many scam victims struggle with the idea that, despite their best efforts, they were exploited by someone who may go unpunished.

Assumptions About Safety and Control

Scam victims often believe that the world is generally safe and that they are in control of their own lives. Scammers, by manipulating trust and emotions, destabilize this sense of control. Victims often feel violated, as though their personal autonomy and ability to protect themselves were taken away by the scammer’s deceit. This loss of control can be traumatic, leading to feelings of vulnerability and fear in future situations. Victims may become hypervigilant, constantly fearing that they will be deceived or exploited again, which can result in anxiety or paranoia in their everyday interactions.

Impact on Recovery

Shattered assumptions not only contribute to the trauma experienced by scam victims but also complicate the recovery process. Victims may resist seeking help or support because their trust in others, including professionals, has been broken. Additionally, their sense of personal failure can lead to isolation, as they may feel too ashamed to reach out for assistance. Rebuilding a sense of trust, confidence, and control is essential for recovery, but it requires victims to confront and reconstruct the beliefs that were shattered during the scam. Therapy, particularly trauma-informed approaches like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), can be instrumental in helping victims rebuild their core assumptions in healthier, more adaptive ways.

The trauma experienced by scam victims is deeply rooted in the shattering of fundamental assumptions about the world, others, and themselves. When these assumptions—such as trust, fairness, and personal competence—are destroyed, victims experience profound emotional and psychological distress. Understanding how these shattered assumptions contribute to trauma is critical for helping victims rebuild their lives and regain a sense of safety, trust, and control.

Emotional Dysregulation and Its Role in Trauma for Scam Victims

Emotional dysregulation refers to the inability to manage or respond to emotional experiences in an appropriate manner. For scam victims, emotional dysregulation plays a significant role in contributing to trauma both during and after the scam. Scammers often exploit their victim’s emotions, manipulating feelings of love, trust, fear, or urgency, which destabilizes the victim’s emotional state. This manipulation results in intense emotional experiences, such as anxiety, anger, guilt, or shame, that the victim is unable to effectively process or control.

Emotional Manipulation by Scammers

During a scam, emotional dysregulation can begin as a direct consequence of the scammer’s tactics. In romance scams, for example, scammers use “love bombing” to overwhelm victims with affection and attention, creating a false sense of connection and trust. As the scam progresses, they might shift tactics, using emotional blackmail, guilt manipulation, or fear to keep the victim engaged and compliant. Victims are constantly subjected to emotional highs and lows—love, fear, desperation, and confusion—which makes it difficult for them to maintain emotional stability. This roller-coaster of emotions overwhelms the victim’s ability to regulate feelings, resulting in heightened stress and emotional vulnerability.

Impact on Emotional Stability

Once the scam is exposed, the emotional dysregulation often intensifies. Victims are left to grapple with feelings of betrayal, humiliation, guilt, and self-blame. Their sense of reality has been manipulated, and they may struggle with recognizing how their emotions were used against them. Victims can experience a flood of conflicting emotions—anger at the scammer, shame for being deceived, and grief over their financial or emotional losses. This state of emotional dysregulation can prevent victims from processing their experiences healthily, leading to prolonged distress, anxiety, or depression. Many victims find it difficult to regain emotional equilibrium, resulting in long-term emotional instability.

Trauma Symptoms and Emotional Dysregulation

Emotional dysregulation is a key factor in the development of trauma symptoms, such as those found in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Victims may become hypervigilant, constantly on edge, and easily triggered by reminders of the scam or interactions that evoke the same emotions. They may also experience emotional numbness or detachment, struggling to connect with others or process their feelings. This inability to regulate emotions can lead to avoidance behaviors, where victims may avoid discussing the scam, seeking help, or engaging in social interactions, further deepening their isolation and sense of helplessness.

Dysregulation’s Impact on Relationships

In the aftermath of a scam, emotional dysregulation can severely impact a victim’s ability to maintain or form new relationships. Victims may have difficulty trusting others, fearing further manipulation or betrayal. They may react with excessive anger or anxiety to situations that remind them of the scam, even if those situations do not warrant such responses. In close relationships, victims may withdraw emotionally or become overly dependent, fearing abandonment or further harm. This pattern of emotional dysregulation can prevent victims from fully recovering, as it perpetuates feelings of fear, mistrust, and emotional instability.

Challenges in Seeking Help

Emotional dysregulation can also hinder victims from seeking support and engaging in the recovery process. The overwhelming emotions of guilt, shame, or embarrassment may prevent them from reaching out to friends, family, or professionals for help. In some cases, victims may lash out at those offering support, feeling misunderstood or judged. This further isolates them and deepens the trauma. Without proper emotional regulation, victims may struggle to articulate their experiences or recognize that they need help, delaying recovery and prolonging emotional suffering.

Role of Therapy in Addressing Emotional Dysregulation

Addressing emotional dysregulation is a critical part of trauma recovery for scam victims. Therapeutic interventions, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) or Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT), are often used to help victims regain control of their emotions. These therapies teach individuals to identify and understand their emotional triggers, develop coping mechanisms, and reframe the way they process emotional stimuli. For scam victims, therapy provides a safe space to express their emotions, process their trauma, and learn how to regulate their emotional responses in a healthier manner, paving the way for emotional stability and recovery.

Emotional dysregulation is a significant contributor to the trauma experienced by scam victims. The intense emotional manipulation by scammers, coupled with the overwhelming feelings of guilt, betrayal, and shame after the scam, leads to difficulty managing emotions. This dysregulation prolongs emotional suffering, affects relationships, and complicates the recovery process. However, with the right therapeutic interventions, scam victims can learn to manage their emotions effectively, reducing the long-term impact of trauma and restoring their emotional well-being.

Schema Conflicts and Their Neurobiological Impact on Scam Victims’ Trauma

When a person’s schema—their internal mental framework about how the world works—clashes with an unexpected and distressing experience, it can have profound neurobiological effects that contribute to trauma. In the context of scam victims, their pre-existing schemas about trust, relationships, or financial security are severely disrupted when they realize they’ve been manipulated and deceived. These schema conflicts trigger a cascade of emotional and physiological responses that contribute to the traumatic experience, leading to significant changes in the brain.

Disruption of Predictive Coding and Emotional Stability

Schemas allow individuals to predict and make sense of the world. When an individual is scammed, their schema of trustworthiness, love, or financial integrity is shattered, causing a disruption in predictive coding—the brain’s ability to predict outcomes based on past experiences. This conflict between expectation and reality leads to confusion, distress, and a sense of betrayal. The brain’s emotional centers, particularly the amygdala, are activated in response to this perceived threat, resulting in heightened fear, anxiety, and stress. Scam victims may experience chronic hyperarousal, where their fight-or-flight response is constantly triggered due to the perceived danger of being deceived again.

Activation of the HPA Axis and Chronic Stress

The conflict between schemas and reality can activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, a central stress response system. When victims realize they’ve been scammed, their brain perceives this as a threat, releasing stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline. Prolonged activation of the HPA axis can lead to chronic stress, which has neurobiological consequences, including impaired cognitive functioning, sleep disturbances, and emotional dysregulation. Scam victims might experience heightened levels of anxiety, depression, and a constant sense of being on edge, all of which are typical trauma symptoms.

Neuroplasticity and the Development of Maladaptive Schemas

Neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to rewire itself, plays a role in how scam victims develop new, maladaptive schemas in response to the trauma. When a traumatic event such as being scammed occurs, the brain rewires itself to protect against future harm, often reinforcing negative schemas like mistrust, self-blame, or fear of vulnerability. These maladaptive schemas can result in victims becoming overly cautious or distrustful, even in situations where trust is warranted, which impairs their ability to form healthy relationships and seek support.

Impact on the Hippocampus and Memory Processing

Trauma caused by schema conflict can affect the hippocampus, a region of the brain responsible for memory formation and contextualizing experiences. Chronic stress and trauma are known to reduce hippocampal volume, impairing the ability to form coherent memories of the scam. Victims may struggle to recall details accurately, experience fragmented memories, or find themselves fixated on certain aspects of the event. This impairment in memory processing further contributes to the confusion and helplessness often experienced by scam victims, as they grapple with the dissonance between their prior beliefs and the reality of the scam.

Emotional Processing in the Amygdala

The amygdala, which is involved in emotional regulation and threat detection, becomes hyperactive in trauma survivors. Scam victims may become emotionally hypersensitive, particularly to situations that remind them of the scam, even if the context is entirely different. This hyperactivity of the amygdala can lead to emotional flashbacks, where the victim re-experiences feelings of shame, guilt, or fear associated with the scam. Over time, this heightened emotional reactivity can make it difficult for victims to regulate their emotions, contributing to feelings of helplessness and the long-lasting effects of trauma.

Schema Conflict and Cognitive Dissonance

The internal conflict between a scam victim’s established schema (e.g., “People who are kind and attentive are trustworthy”) and the reality that they were deceived creates a state of cognitive dissonance. This dissonance, or the discomfort of holding contradictory beliefs, forces the brain to resolve the conflict either by rejecting the new reality or by painfully restructuring the schema to accommodate the new information. Resolving this conflict often requires victims to confront deeply distressing truths about themselves, their judgment, or their vulnerability, which can be emotionally overwhelming and contribute to the development of trauma.

Interference with Future Decision-Making

Once a scam victim’s schemas are shattered, their ability to trust their own decision-making is often compromised. The brain, in an attempt to protect itself from future harm, may overcompensate by creating rigid, overly cautious schemas that impair the victim’s ability to assess new situations rationally. This can lead to avoidance behaviors, where victims shy away from financial decisions, relationships, or opportunities due to the fear of being deceived again. Over time, this hypervigilance and emotional withdrawal can significantly impact their quality of life, reinforcing the trauma and making recovery more challenging.

The neurobiological impact of schema conflicts is a key factor in the trauma experienced by scam victims. The brain’s emotional, cognitive, and stress-response systems become overwhelmed when faced with the dissonance between trusted mental models and the harsh reality of deception. This leads to lasting changes in emotional regulation, memory processing, and decision-making, all of which contribute to the long-term effects of trauma. By understanding the role of schemas in trauma, victims and professionals can work toward developing therapeutic strategies to help victims rebuild trust, reframe their mental models, and heal from the neurobiological consequences of the scam.

Protective Maladaptive Schemas in Scam Victims

When scam victims experience a significant conflict between their pre-existing schemas (such as trust in relationships or financial security) and the traumatic reality of being deceived, their minds often respond by developing protective maladaptive schemas as a defense mechanism. These maladaptive schemas are cognitive frameworks that evolve to shield the individual from further emotional harm but ultimately contribute to their ongoing trauma and hinder recovery.

Development of Distrust and Hypervigilance

One of the most common protective maladaptive schemas is distrust/abuse, where the victim starts to believe that others cannot be trusted and that people are inherently manipulative or abusive. After being scammed, individuals may shift from a schema of trust and openness to one of constant suspicion. This hypervigilant state is designed to protect the victim from future scams but can interfere with healthy relationships and interactions. The fear of being deceived again can prevent scam victims from forming new bonds, further isolating them and compounding their emotional distress.

Emotional Deprivation and Avoidance

Scam victims often develop a schema of emotional deprivation, where they believe their emotional needs will never be met or that seeking emotional support is futile. This protective schema can stem from the emotional manipulation they experienced during the scam, where they invested trust, affection, or financial resources, only to have these needs betrayed. As a result, victims may avoid future emotional investments, relationships, or seeking help, believing that vulnerability will only lead to more pain. While this schema aims to prevent further emotional harm, it leads to isolation and a lack of social support, which are crucial for recovery.

Helplessness and Subjugation

Some victims develop a helplessness or subjugation schema, where they feel powerless or incapable of protecting themselves. This schema may emerge when victims believe they could not have done anything to avoid the scam, reinforcing a sense of vulnerability. The result is a feeling of being trapped or controlled, which scammers exploit through emotional manipulation or coercion. Over time, this helplessness leads to an avoidance of responsibility or decision-making, further entrenching the victim’s trauma and making them more susceptible to further manipulation in the future.

Punitiveness and Self-Blame

Another form of protective maladaptive schema is punitiveness or self-blame, where the victim internalizes the scam as their own fault. This schema may emerge as a way to regain control—if the victim believes they are responsible for their situation, they might think they can avoid future harm by being more cautious. However, this belief often spirals into self-criticism, guilt, and low self-esteem. Victims may become harshly judgmental of themselves, reinforcing negative thoughts and behaviors, which contribute to feelings of shame and further emotional suffering.

Fear of Vulnerability

Scam victims might also develop a fear of vulnerability schema, where they perceive that opening up emotionally or trusting others again will only lead to harm. This schema protects the individual by keeping others at a distance, but it also prevents them from engaging in meaningful relationships or seeking the help they need. This avoidance of vulnerability can perpetuate feelings of loneliness, anxiety, and distrust, making it difficult for victims to heal and move forward.

Exaggerated Control and Autonomy

Some scam victims may develop a schema of exaggerated control, where they believe they must control every aspect of their environment to prevent future harm. This may manifest as obsessive behaviors, such as micromanaging finances or becoming overly cautious in social situations. While this schema serves as a protective mechanism, it can lead to an inability to relax or trust others, resulting in heightened anxiety and emotional exhaustion.

The development of protective maladaptive schemas is a natural psychological response to the trauma of being scammed, but these schemas ultimately contribute to the victim’s continued suffering. They create cognitive and emotional barriers that prevent victims from forming new relationships, seeking help, or trusting themselves. In order to recover, victims need to recognize these maladaptive schemas and work through them, often with the help of therapy, to rebuild healthier cognitive frameworks that support healing and emotional well-being.

Conclusion

When deeply held schemas (mental models or cognitive frameworks) are confronted by experiences that directly contradict them, a profound psychological disturbance can occur, leading to trauma. Schemas help individuals organize and interpret their world, often giving them a sense of security and predictability. When an experience challenges these schemas, the individual is forced to confront conflicting realities, which can lead to cognitive dissonance—a state of mental discomfort resulting from holding two opposing beliefs or realities simultaneously.

The severity of the trauma depends largely on the individual’s ability to process, integrate, or adjust their schemas to accommodate the new information. For some, this dissonance is manageable, allowing them to adapt their worldview and minimize the trauma. However, for others, especially those with rigid or deeply ingrained schemas, this conflict can feel overwhelming, leading to emotional distress, confusion, and an inability to reconcile the discrepancy. This process can shatter their psychological equilibrium, creating an emotional crisis or trauma.

For instance, in the context of scams, if someone has a deeply held schema that people they form emotional or financial bonds with are trustworthy, discovering that they’ve been deceived by a scammer contradicts this fundamental belief. The resulting cognitive dissonance can trigger trauma because the victim’s understanding of trust, relationships, and self-judgment has been violated. The inability to reconcile the fact that they believed in the scam with the reality that it was a lie can lead to intense feelings of betrayal, self-blame, and psychological distress.

Therapeutic Approaches

To help individuals resolve these conflicts and recover from trauma, therapeutic approaches such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Schema Therapy are often used. These therapies focus on identifying, understanding, and reframing maladaptive schemas to develop healthier mental frameworks:

-

-

- CBT works by challenging and restructuring distorted thoughts that arise from maladaptive schemas, helping individuals replace harmful thought patterns with more adaptive ones. For scam victims, this might involve addressing feelings of guilt or shame and helping them realize they were manipulated by professionals, not failing in judgment.

- Schema Therapy delves deeper into identifying long-standing patterns of thinking that originated in early life and might have predisposed an individual to fall for a scam (e.g., schemas of abandonment, mistrust, or defectiveness). Through this therapy, individuals can reprocess these schemas, helping them rebuild their sense of self-worth and resilience.

-

Both therapies aim to reconcile the conflicting experience with a more adaptable schema, reducing the emotional toll of the trauma. By engaging in these therapeutic interventions, individuals can better manage cognitive dissonance, regain emotional balance, and reconstruct a more realistic understanding of relationships and trust.

Reference

- Schematic integration of traumatic events – SEE PDF

- Associations between trauma, early maladaptive schemas

- Investigating the schema modes in individuals with traumatic experiences through the lens of object relations model: A narrative review

- Early maladaptive schemas in adult survivors of interpersonal trauma: foundations for a cognitive theory of psychopathology

- Maladaptive Schemas in Survivors of Interpersonal Trauma

- Deconstructing Trauma Schemas

- Schema therapy for complex trauma survivors

- Relationships between Childhood Traumatic Experiences, Early Maladaptive Schemas and Interpersonal Styles

SCARS Institute Podcast

Schema Conflict Theory

SCARS Institute Podcast

Introduction to Schemas

-/ 30 /-

What do you think about this?

Please share your thoughts in a comment below!

A Note About Labeling!

We often use the term ‘scam victim’ in our articles, but this is a convenience to help those searching for information in search engines like Google. It is just a convenience and has no deeper meaning. If you have come through such an experience, YOU are a Survivor! It was not your fault. You are not alone! Axios!

Statement About Victim Blaming

SCARS Institute articles examine different aspects of the scam victim experience, as well as those who may have been secondary victims. This work focuses on understanding victimization through the science of victimology, including common psychological and behavioral responses. The purpose is to help victims and survivors understand why these crimes occurred, reduce shame and self-blame, strengthen recovery programs and victim opportunities, and lower the risk of future victimization.

At times, these discussions may sound uncomfortable, overwhelming, or may be mistaken for blame. They are not. Scam victims are never blamed. Our goal is to explain the mechanisms of deception and the human responses that scammers exploit, and the processes that occur after the scam ends, so victims can better understand what happened to them and why it felt convincing at the time, and what the path looks like going forward.

Articles that address the psychology, neurology, physiology, and other characteristics of scams and the victim experience recognize that all people share cognitive and emotional traits that can be manipulated under the right conditions. These characteristics are not flaws. They are normal human functions that criminals deliberately exploit. Victims typically have little awareness of these mechanisms while a scam is unfolding and a very limited ability to control them. Awareness often comes only after the harm has occurred.

By explaining these processes, these articles help victims make sense of their experiences, understand common post-scam reactions, and identify ways to protect themselves moving forward. This knowledge supports recovery by replacing confusion and self-blame with clarity, context, and self-compassion.

Additional educational material on these topics is available at ScamPsychology.org – ScamsNOW.com and other SCARS Institute websites.

-/ 30 /-

What do you think about this?

Please share your thoughts in a comment below!

Important Information for New Scam Victims

- Please visit www.ScamVictimsSupport.org – a SCARS Website for New Scam Victims & Sextortion Victims.

- SCARS Institute now offers its free, safe, and private Scam Survivor’s Support Community at www.SCARScommunity.org – this is not on a social media platform, it is our own safe & secure platform created by the SCARS Institute especially for scam victims & survivors.

- SCARS Institute now offers a free recovery learning program at www.SCARSeducation.org.

- Please visit www.ScamPsychology.org – to more fully understand the psychological concepts involved in scams and scam victim recovery.

If you are looking for local trauma counselors, please visit counseling.AgainstScams.org

If you need to speak with someone now, you can dial 988 or find phone numbers for crisis hotlines all around the world here: www.opencounseling.com/suicide-hotlines

Statement About Victim Blaming

Some of our articles discuss various aspects of victims. This is both about better understanding victims (the science of victimology) and their behaviors and psychology. This helps us to educate victims/survivors about why these crimes happened and not to blame themselves, better develop recovery programs, and help victims avoid scams in the future. At times, this may sound like blaming the victim, but it does not blame scam victims; we are simply explaining the hows and whys of the experience victims have.

These articles, about the Psychology of Scams or Victim Psychology – meaning that all humans have psychological or cognitive characteristics in common that can either be exploited or work against us – help us all to understand the unique challenges victims face before, during, and after scams, fraud, or cybercrimes. These sometimes talk about some of the vulnerabilities the scammers exploit. Victims rarely have control of them or are even aware of them, until something like a scam happens, and then they can learn how their mind works and how to overcome these mechanisms.

Articles like these help victims and others understand these processes and how to help prevent them from being exploited again or to help them recover more easily by understanding their post-scam behaviors. Learn more about the Psychology of Scams at www.ScamPsychology.org

SCARS INSTITUTE RESOURCES:

If You Have Been Victimized By A Scam Or Cybercrime

♦ If you are a victim of scams, go to www.ScamVictimsSupport.org for real knowledge and help

♦ SCARS Institute now offers its free, safe, and private Scam Survivor’s Support Community at www.SCARScommunity.org/register – this is not on a social media platform, it is our own safe & secure platform created by the SCARS Institute especially for scam victims & survivors.

♦ Enroll in SCARS Scam Survivor’s School now at www.SCARSeducation.org

♦ To report criminals, visit https://reporting.AgainstScams.org – we will NEVER give your data to money recovery companies like some do!

♦ Follow us and find our podcasts, webinars, and helpful videos on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@RomancescamsNowcom

♦ Learn about the Psychology of Scams at www.ScamPsychology.org

♦ Dig deeper into the reality of scams, fraud, and cybercrime at www.ScamsNOW.com and www.RomanceScamsNOW.com

♦ Scam Survivor’s Stories: www.ScamSurvivorStories.org

♦ For Scam Victim Advocates visit www.ScamVictimsAdvocates.org

♦ See more scammer photos on www.ScammerPhotos.com

You can also find the SCARS Institute’s knowledge and information on Facebook, Instagram, X, LinkedIn, and TruthSocial

Psychology Disclaimer:

All articles about psychology and the human brain on this website are for information & education only

The information provided in this and other SCARS articles are intended for educational and self-help purposes only and should not be construed as a substitute for professional therapy or counseling.

Note about Mindfulness: Mindfulness practices have the potential to create psychological distress for some individuals. Please consult a mental health professional or experienced meditation instructor for guidance should you encounter difficulties.

While any self-help techniques outlined herein may be beneficial for scam victims seeking to recover from their experience and move towards recovery, it is important to consult with a qualified mental health professional before initiating any course of action. Each individual’s experience and needs are unique, and what works for one person may not be suitable for another.

Additionally, any approach may not be appropriate for individuals with certain pre-existing mental health conditions or trauma histories. It is advisable to seek guidance from a licensed therapist or counselor who can provide personalized support, guidance, and treatment tailored to your specific needs.

If you are experiencing significant distress or emotional difficulties related to a scam or other traumatic event, please consult your doctor or mental health provider for appropriate care and support.

Also read our SCARS Institute Statement about Professional Care for Scam Victims – click here

If you are in crisis, feeling desperate, or in despair, please call 988 or your local crisis hotline – international numbers here.

More ScamsNOW.com Articles

A Question of Trust

At the SCARS Institute, we invite you to do your own research on the topics we speak about and publish. Our team investigates the subject being discussed, especially when it comes to understanding the scam victims-survivors’ experience. You can do Google searches, but in many cases, you will have to wade through scientific papers and studies. However, remember that biases and perspectives matter and influence the outcome. Regardless, we encourage you to explore these topics as thoroughly as you can for your own awareness.

![NavyLogo@4x-81[1] Schemas Part 4: SCARS Institute Theory - Schema Conflict Resulting in Psychological Trauma - 2024](https://scamsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/NavyLogo@4x-811.png)

![scars-institute[1] Schemas Part 4: SCARS Institute Theory - Schema Conflict Resulting in Psychological Trauma - 2024](https://scamsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/scars-institute1.png)

![niprc1.png1_-150×1501-1[1] Schemas Part 4: SCARS Institute Theory - Schema Conflict Resulting in Psychological Trauma - 2024](https://scamsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/niprc1.png1_-150x1501-11.webp)